- Home

- Vladimir Putin

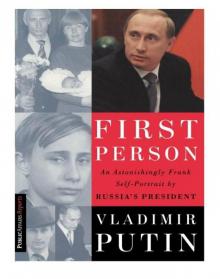

First Person

First Person Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Preface

Principle Figures in First Person

Part I - THE SON

Part 2 - THE SCHOOLBOY

Part 3 - THE UNIVERSITY STUDENT

Part 4 - THE YOUNG SPECIALIST

Part 5 - THE SPY

Part 6 - THE DEMOCRAT

Part 7 - THE BUREAUCRAT

Part 8 - THE FAMILY MAN: INTERVIEW WITH LYUDMILA PUTINA

Part 9 - THE POLITICIAN

Copyright Page

Preface

We talked with Vladimir Putin on six separate occasions, for about four hours at a time. Both he and we were patient and tolerant; he, when we asked uncomfortable questions or were too invasive; we, when he was late or asked us to turn the tape recorder off. “That’s very personal,” he would say.

These were meetings “with our jackets off,” although we all still wore ties. Usually they happened late at night. And we only went to his office in the Kremlin once.

Why did we do this? Essentially, we wanted to answer the same question that Trudy Rubin of the Philadelphia Inquirer asked in Davos in January: “Who is Putin?” Rubin’s question had been addressed to a gathering of prominent Russian politicians and businessmen. And instead of an answer, there was a pause.

We felt that the pause dragged on too long. And it was a legitimate question. Who was this Mr. Putin?

We talked to Putin about his life. We talked—as people often do in Russia—around the dinner table. Sometimes he arrived exhausted, with drooping eyelids, but he never broke off the conversation. Only once, when it was well past midnight, did he ask politely, “Well then, have you run out of questions, or shall we chat some more?”

Sometimes Putin would pause a while to think about a question, but he would always answer it eventually. For example, when we asked whether he had ever been betrayed, he was silent a long time. Finally, he decided to say “no,” but then added by way of clarification, “My friends didn’t betray me.”

We sought out Putin’s friends, people who know him well or who have played an important role in his destiny. We went out to his dacha, where we found a bevy of women: his wife, Lyudmila, two daughters—Masha and Katya—and a poodle with a hint of the toy dog in her, named Toska.

We have not added a single editorial line in the book. It holds only our questions. And if those questions led Putin or his relatives to reminisce or ponder, we tried not to interrupt. That’s why the book’s format is a bit unusual—it consists entirely of interviews and monologues.

All of our conversations are recorded in these pages. They might not answer the complex question of “Who is this Mr. Putin?,” but at least they will bring us a little bit closer to understanding Russia’s newest president.

NATALIYA GEVORKYAN

NATALYA TIMAKOVA

ANDREI KOLESNIKOV

Principle Figures in First Person

People

VADIM VIKTOROVICH BAKATIN:

USSR interior minister (1988—90); chairman of KGB (1991); presidential candidate.

BORIS ABRAMOVICH BEREZOVSKY:

Prominent businessman influential in political affairs; part-owner of ORT, pro-government public television station; former deputy secretary of Security Council, October 1996—November 1997; involved in the Chechen conflict; appointed executive secretary of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS); dismissed by Yeltsin in March 1999, elected member of parliament from Karachaevo-Cherkessia in December 1999.

PAVEL PAVLOVICH BORODIN:

Chief of staff in the presidential administration from 1993 to 2000; In January 2000, appointed state secretary of the Union of Belarus and Russia.

LEONID ILYICH BREZHNEV:

General secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964—1982.

ANATOLY BORISOVICH CHUBAIS:

Vice premier in the Chernomyrdin government (1992) and government (1994); appointed member of the government commission handling privatization and structural adjustment in 1993; appointed first deputy chair of the government in 1994 and dismissed by Yeltsin in January 1996; appointed by Yeltsin to post of chief of presidential administration in July 1996; Minister of Finance, March—November 1997.

VLADIMIR CHUROV:

Deputy chair of the Committee for Foreign Liason of the St. Petersburg Mayor’s Office in Sobchak administration.

MICHAEL FROLOV:

Retired colonel, Putin’s instructor at the Andropov Red Banner Institute.

VERA DMITRIEVNA GUREVICH:

Putin’s schoolteacher from grades 4 to 8 in School No. 193 in St. Petersburg.

SERGEI BORISOVICH IVANOV:

Foreign intelligence career officer with rank of lieutenant general; appointed deputy director of FSB in August 1998; appointed secretary of the Security Council in November 1999.

KATYA:

Putin’s younger daughter.

SERGEI VLADILENOVICH KIRIENKO:

First deputy minister of energy in 1997; appointed chair of the government (prime minister) in April 1998 and dismissed by Yeltsin in August 1998, elected member of parliament from the party list of the Union of Right Forces.

ALEKSANDR VASILYEVICH KORZHAKOV:

Hired as Boris Yeltsin’s bodyguard in 1985 when Yeltsin was first secretary of the Moscow City Party Committee and continued to manage Yeltsin’s security in subsequent positions; awarded the rank of general in 1992; joined the Yeltsin election campaign in 1996 and was dismissed from all his posts in June 1996 after disagreements about how to run the campaign.

VLADIMIR ALEKSANDROVICH KRYUCHKOV:

Chairman of the Soviet KGB (1988—91) until arrested for the August 1991 coup; amnestied in February 1994.

YURI LUZHKOV:

Mayor of Moscow.

MASHA:

Putin’s older daughter.

YEVGENY MAKSIMOVICH PRIMAKOV:

Pravda columnist and former director of the USSR Institute of Oriental Studies and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations, first deputy chairman of the KGB (1991), director of the Soviet Central Intelligence Service (1991), and then director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (1991—1996); appointed Foreign Minister January 1996 and again in 1998; appointed by Yeltsin’s decree to the position of chair of the government (prime minister) in September 1998 and dismissed by Yeltsin from this position in May 1999; elected to the State Duma (parliament) from the party list of Fatherland—All Russia in December 1999.

LYUDMILA PUTINA:

Vladimir Putin’s wife (nicknames found in text: Luda, Ludik).

SERGEI ROLDUGIN:

Lead cellist in the Mariinsky Theater Symphony Orchestra, a friend of the Putins, and godfather of Putin’s older daughter, Masha.

EDUARD AMVROSIEVICH SHEVARDNADZE:

Soviet foreign minister (1985—91) who resigned in protest of the impending coup; co-chairman of Democratic Reform Movement (1991—92); head of state and chairman of parliament of Georgia.

ANATOLY ALEKSANDROVICH SOBCHAK:

Mayor and chair of the government of St. Petersburg (Leningrad) from 1991 to 1996; co-chairman of Democratic Reform Movement (1991—92); member of the Russian Presidential Council since 1992; died in February 2000. His wife is Lyudmila Borisnova.

OLEG NIKOLAYEVICH SOSKOVETS:

Appointed first deputy chair of the government in 1993 (deputy prime minister) responsible for 14 ministries, including energy and transportation; assigned to deal with the Chechen conflict in 1994; joined Yeltsin presidential campaign team in 1996 but dismissed in March from the campaign, and, in June, was relieved of his post as first vice premier.

YURI SKURATOV:

Former Prosecutor General, suspended after a newspaper published a photograph of h

im in a steam bath with two prostitutes.

VLADIMIR ANATOLYEVICH YAKOVLEV:

First deputy mayor of St. Petersburg from 1993—1996; elected governor of St. Petersburg in 1996.

MARINA YENTALTSEVA:

Putin’s secretary at the St. Petersburg City Council (1991—96).

VALENTIN YUMASHEV:

Chief of staff in the Yeltsin administration

Terms

FRG Federal Republic of Germany

FSB Federal Security Service

FSK Federal Counterintelligence Service

FSO Federal Guard Servic

GDR German Democratic Republic (East Germany)

KGB Committee for State Security (Soviet era)

Komsomol Young Communist League

Kukly Puppets, a satirical TV show

MVD Ministry of Internal Affairs or Interior Min istry

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NKVD People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, or the Stalin-era secret police

OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, 54-member security and human rights body founded in 1975.

Pioneers Soviet-era children’s organization

SED East German Communist Party

“In fact, I have had a very simple life. Everything is an open book.

I finished school and went to university.

I graduated from university and went to the KGB.

I finished the KGB and went back to university.

After university, I went to work for Sobchak.

From Sobchak, to Moscow and to the General Department.

Then to the Presidential Administration.

From there, to the FSB.

Then I was appointed Prime Minister.

“Now I’m Acting President. That’s it!”

“But surely there are more details?”

“Yes, there are. . . .”

Part I

THE SON

Putin talks about his parents, touching on his father’s World War II sabotage missions, the Siege of Leningrad, and life in a communal flat after the war. It isn’t easy—no hot water, no bathroom, a stinking toilet, and constant bickering. Putin spends much of his time chasing rats with a stick in the stairwell.

I know more about my father’s family than about my mother’s. My father’s father was born in St. Petersburg and worked as a cook. They were a very ordinary family. A cook, after all, is a cook. But apparently my grandfather cooked rather well, because after World War I he was offered a job in The Hills district on the outskirts of Moscow, where Lenin and the whole Ulyanov family lived. When Lenin died, my grandfather was transferred to one of Stalin’s dachas. He worked there a long time.

He wasn’t a victim of the purges?

No, for some reason they let him be. Few people who spent much time around Stalin came through unscathed, but my grandfather was one of them. He outlived Stalin, by the way, and in his later, retirement years he was a cook at the Moscow City Party Committee sanitorium in Ilinskoye.

Did your parents talk much about your grandfather?

I have a clear recollection of Ilinskoye myself, because I used to come for visits. My grandfather kept pretty quiet about his past life. My parents didn’t talk much about the past, either. People generally didn’t, back then. But when relatives would come to visit, there would be long chats around the table, and I would catch some snatches, some fragments of the conversation. But my parents never told me anything about themselves. Especially my father. He was a silent man.

I know my father was born in St. Petersburg in 1911. After World War I broke out, life was hard in the city. People were starving. The whole family moved to my grandmother’s home in the village of Pominovo, in the Tver region. Her house is still standing today, by the way; members of the family still spend their vacations there. It was in Pominovo that my father met my mother. They were both 17 years old when they got married.

Why? Did they have a reason to?

No, apparently not. Do you need a reason to get married? The main reason was love. And my father was headed for the army soon. Maybe they each wanted some sort of guarantee. . . . I don’t know.

Vera Dmitrievna Gurevich (Vladimir Putin’s schoolteacher from grades 4 through 8 in School No. 193):

Volodya’s1 parents had a very difficult life. Can you imagine how courageous his mother must have been to give birth at age 41? Volodya’s father once said to me, “One of our sons would have been your age.” I assumed they must have lost another child during the war, but didn’t feel comfortable asking about it.

In 1932, Putin’s parents came to Peter [St. Petersburg]. They lived in the suburbs, in Peterhof. His mother went to work in a factory and his father was almost immediately drafted into the army, where he served on a submarine fleet. Within a year after he returned, they had two sons. One died a few months after birth.

Apparently, when the war broke out, your father went immediately to the front. He was a submariner who had just completed his term of service . . .

Yes, he went to the front as a volunteer.

And your mama?

Mama categorically refused to go anywhere. She stayed at home in Peterhof. When it became extremely hard to go on there, her brother in Peter took her in. He was a naval officer serving at the fleet’s headquarters in Smolny.2 He came for her and the baby and got them out under gunfire and bombs.

And what about your grandfather, the cook? Didn’t he do anything to help them?

No. Back then, people generally didn’t ask for favors. I think that under the circumstances it would have been impossible, anyway. My grandfather had a lot of children, and all of his sons were at the front.

So your mother and brother were taken from Peterhof, which was under blockade, to Leningrad, which was also blockaded ?

Where else could they go? Mama said that some sort of shelters were being set up in Leningrad, in an effort to save the children’s lives. It was in one of those children’s homes that my second brother came down with diphtheria and died.

How did she survive?

My uncle helped her. He would feed her out of his own rations. There was a time when he was transferred somewhere for a while, and she was on the verge of starvation. This is no exaggeration. Once my mother fainted from hunger. People thought she had died, and they laid her out with the corpses. Luckily Mama woke up in time and started moaning. By some miracle, she lived. She made it through the entire blockade of Leningrad. They didn’t get her out until the danger was past.

And where was your father?

My father was in the battlefield the whole time. He had been assigned to a demolitions battalion of the NKVD. These battalions were engaged in sabotage behind German lines. My father took part in one such operation. There were 28 people in his group. They were dropped into Kingisepp. They took a good look around, set up a position in the forest, and even managed to blow up a munitions depot before they ran out of food. They came across some local residents, Estonians, who brought them food but later gave them up to the Germans.

They had almost no chance of surviving. The Germans had them surrounded on all sides, and only a few people, including my father, managed to break out. Then the chase was on. The remnants of the unit headed off toward the front line. They lost a few more people along the road and decided to split up. My father jumped into a swamp over his head and breathed through a hollow reed until the dogs had passed by. That’s how he survived. Only 4 of the 28 men in his unit made it back home.

Then he found your mother? They were reunited?

No, he didn’t get a chance to look for her. They sent him right back into combat. He wound up in another tight spot, the so-called Neva Nickel. This was a small, circular area. If you stand with your back to Lake Ladoga, it’s on the left bank of the Neva River. The German troops had seized everything except for this small plot of land. And our guys held that spot through the entire blockade, calculating that it would play a role in the final breakth

rough. The Germans kept trying to capture it. A fantastic number of bombs were dropped on every square meter of that bit of turf—even by the standards of that war. It was a monstrous massacre. But to be sure, the Neva Nickel played an important role in the end.

Don’t you think that we paid too high a price for that little piece of land?

I think that there are always a lot of mistakes made in war. That’s inevitable. But when you are fighting, if you keep thinking that everybody around you is always making mistakes, you’ll never win. You have to take a pragmatic attitude. And you have to keep thinking of victory. And they were thinking of victory then.

First Person

First Person